About

Each day in 2024, I read the Chicago Tribune from the corresponding day in 1924. I did this to learn what Chicagoans were thinking and talking about in real time as events unfolded that continue to shape our present.

The year 1924 was big for Chicago, as big as 1871, 1893, and 1968. This daily reading has led to a weekly blog, social media posts, and a seminar at the Newberry Library.

All photographs courtesy of the Chicago Tribune. No sales, no distribution, no digital manipulation permitted. A big thank you to the Tribune, especially Marianne Mather and Kori Rumore, for their support of this project!

Week One: December 31, 1923-January 5, 1924

1924 started cold and violent. The mercury dipped below zero at 3am on the first of the year and continued to drop steadily, approaching a new record. Several Chicagoans froze to death, including John J. Quirk, whose body was recovered close to the lake, at the 79th Street beach.

As reported in the Chicago Tribune, almost a million Chicagoans stayed up late on December 31, 1923 to welcome in this new year. Hotels like the Congress and Drake drew thousands to their festivities, while many other Chicagoans celebrated quietly at home. Champagne appeared to be in short supply, with national prohibition now entering its fourth year, but revelers had access to “synthetic gin,” bourbon from pharmacies, and bootlegged Canadian whisky.

In the comic strip The Gumps, poor Andy Gump got so drunk on “sympathetic gin” early in the evening that he passes out during the party at the Chez Paree, much to the consternation of his long-suffering wife. He wakes calling out her name in the early morning hours in an empty ballroom.

The police reported arresting six drunks in the Loop. Four Chicagoans suffered gunshot wounds sustained accidentally when neighbors fired off random shots of joy. One of the victims, a woman, was peeling potatoes in her kitchen at the time.

As the temperature dipped, Chicagoans could get the blood pumping by reading about conflict and mayhem around the world and at home. In Washington, a rift had emerged in the governing Republican Party between the conservative President Calvin Coolidge (who had assumed office in August after the death of Warren G. Harding) and the progressive Senator Hiram Johnson of California, that threatened to disrupt the national convention later that year, while a House Committee quietly approved sending to the floor a new immigration bill that would radically impact the demographics of the country.

Abroad, the Mexican government attempted to quell another revolution, war seemed imminent in the Balkans, and the Tories and Liberals plotted a coup to keep the Labour Party, suspected of “Bolshevikism,” out of power in England. All these stories, with a few exceptions, appeared below the fold or within the interior of the Tribune that first week. The above the fold story concerned a scandal in Hollywood.

In that first week of 1924, for three straight days the Tribune reported on the tribulations of actress Mabel Normand, frequent costar of Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle and Charlie Chaplin, who had been in the wrong place at the wrong time on the first of the year. She had been driven to the rented apartment of a transplant from Denver, Courtland Dines, who’d made his money in oil and become involved with a friend of Normand’s, fellow actress Edna Purviance. All the official reports agree that a lot of drinking ensued, as Normand and Purviance were still intoxicated when taken to be questioned by the police later that evening.

At some point, when Normand was in a back bedroom powdering her nose alongside Purviance—or was she on the sofa in the front room talking to Dines, who stood behind the bar or was she, as her chauffeur maintained, attempting to leave but Dines wouldn’t let her and became violent—at some point, this is known: Normand’s chauffeur shot Dines and then calmly called the police to report what he had done, claiming it was to protect a woman’s honor.

Dines would be found in the back bedroom, groaning and clutching his gut, and be taken to Good Samaritan hospital where, within a day, Normand joined him, to receive an emergency appendectomy. As a result of the scandal, the second shooting in as many years involving Normand, picture houses across the nation announced they were pulling her films. In Chicago, during that first week of 1924, her film The Extra Girl screened at the Orpheum, at State and Monroe.

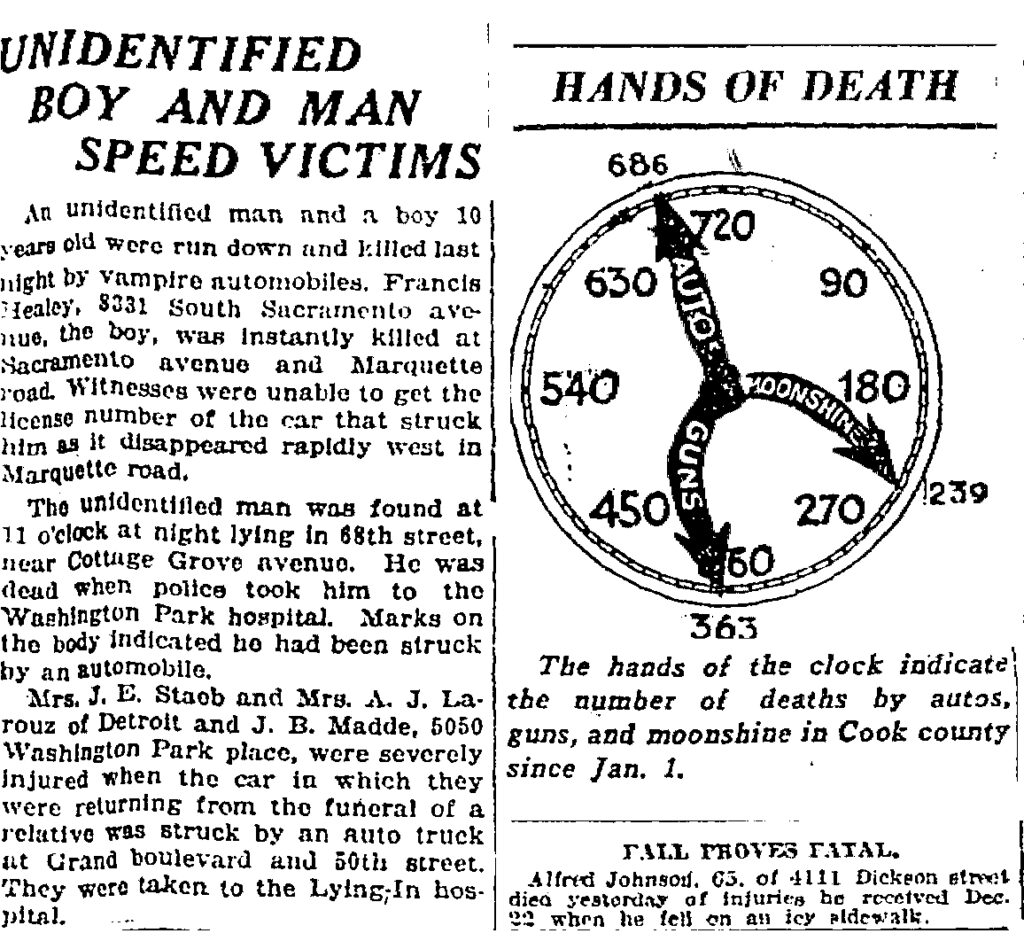

The country’s second largest city had several scandals of its own unfolding over the week. The Tribune intended to create one by listing each day a steadily growing number of automobile-related fatalities; one of the first issues of the new year included a supplement that was little more than a roll call of the over 700 Chicagoans who had died by car in 1923.

Albert Klein, a teacher at the Parental School, a reform school for boys, turned to the courts for protection when he was terminated, he claimed, for having testified about abuses there at an earlier trial, setting up a conflict between the city’s school board and the judge who’d pledged to shield him from retaliation.

The most sensational case at the start of the year mirrored the Dines shooting—like that Hollywood scandal, it involved booze, changing testimony, and perhaps romantic jealousy. On the first of the year police officer John Mulcahy shot and killed Jenny Plarr, 22, an employee at Al Tearney’s cafe and the Cocoanut Grove cabaret, while the two of them were drinking with police officer J.L. Kelly in the back room of Thomas Gilligan’s cigar shop in Woodlawn.

Mulcahy claimed it was an accident but not before switching revolvers with Kelly, evidence in the eyes of Police Chief Morgan Collins of a “coverup.” Both men were drunk at the time of the shooting, and the cigar store was known to be a front for illegal drinking. Mulcahy had married a month prior and met Plarr for the first time that evening as she left the Cocoanut Grove, offering to walk her home before persuading her to slip into the cigar store and join him for a drink. Wounds on Plarr’s hands suggested to the deputy coroner that perhaps the shooting was a result of Mulcahy playing with the gun before it accidentally went off.

The deputy coroner went to great lengths at the inquest to convince the jury that the shooting was an accident, going so far as to interrupt their closed door deliberations so that he could impugn, without evidence, Plarr’s character. It worked, and the jury “absolved” Mulcahy of any “criminal responsibility” in the death. An infuriated Chief Collins vowed there would be consequences for the two officers regardless of the verdict.

“What is behind all this unseemly rush to exonerate a drunken, killing policeman?” Collins fumed. “Is human life so cheap in Chicago as all that?”

Week Two: January 6-January 12, 1924

Ice skating season started in the lagoons of Humboldt Park in the second week of 1924. The city’s best skaters had already departed for the winter Olympics in Chamonix, but scores of others turned up on the ice to welcome back one of the pleasures of the season. This followed after forty-eight hours of intense cold, resulting in the death of seventeen Chicagoans from exposure.

A 4-11 fire broke out in a Loop warehouse late in the week, with the smoke clearing the theaters along Randolph Street, while the curious paid transit fare simply so they could view the conflagration from the safety of nearby L stations.

Heat of a metaphorical kind filled the pages of the Tribune that week, with Sun Yat-Sen’s government in Canton calling for “world revolution” against Western powers and Japan, while stateside the popular twice-married short story writer Nina Putnam faced public accusations of adultery from the wife of her housepainter.

Out in Hollywood, the chauffeur of actress Mabel Normand pleaded self defense in the shooting of Courtland Dines on New Year’s Eve, as prohibition agents looked into the drinking that preceded the incident and the states of Massachusetts, Ohio, and Michigan banned screenings of her films. Asked by the Tribune’s Inquiring Reporter about these bans, Chicagoans seemed more sympathetic to the actress, unless found culpable through a court other than the one of public opinion.

At the Hamilton Club of Chicago, the solicitor general of the United States, James M. Beck proclaimed that the “greatest curse of our nation today is our moving picture mind,” where “we cannot hold any lasting impressions,” and, therefore, are incapable of making informed decisions, whether in regard to politics or ethics. In addition to moving pictures, Beck blamed newspapers and the radio for the nation having lost its “sense of values.”

This loss of values had been on display the previous week when a grand jury had cleared Officer John Mulcahy of any wrongdoing in the shooting death of cabaret employee Jenny Plarr with surprising rapidity. Encouraged by Police Chief Morgan Collins, Coroner Oscar Wolff empaneled a new jury who determined that Mulcahy had committed involuntary manslaughter.

A different police officer was cleared in the fatal shooting of Lane Tech high school honor student Waldemar Linne Lindgren that week, having claimed to have mistaken the boy for a burglar skulking outside the former’s front window. “I told him I was an officer and told him to hold up his hands,” explained Officer Walter Ficther, “He ran. I fired once into the air, then three shots at him.” No evidence found on Lindgren’s body suggested he was attempting a burglary, while his father maintained, “He was a model boy. He wouldn’t do no wrong.”

A day after Officer Ficther was cleared, Betty Michaelson, 19, began a thirty-day sentence in the county jail for having shot and wounded her husband. As she scrubbed the floors of the various cells, the Tribune reporter noted that it was mud tracked by Michaelson’s husband across the clean floors of her kitchen that had led to his shooting.

As part of a series of articles focused on the rising level of gun violence, journalist Arthur Evans noted that Chicago had strict laws in place, but “Evanston, Harvey, Gary, a long string of other suburban towns, are delivery points of easy access.” Gang members engaged in the illicit booze trade knew all the loopholes and used them to their advantage. Only “action on a nation-wide scale” could lessen gun violence. The next in the series promised to consider the “pistol vs. shotgun as a home defender, with some observations on the ‘right to bear arms’ provision in the federal constitution.”

Week Three: January 13-January 19, 1924

Headlines in the Tribune in the third week of 1924 grabbed readers with scandals old and new. The strange story of Warren J. Lincoln, a lawyer and floriculturist from Aurora, resumed when the man—who had months earlier disappeared, having been presumed murdered by his wife and brother-in-law, only to turn up alive and vanish again—reappeared. This time authorities arrested him on suspicion of having slain those accused of killing him.

In Oak Park, a married Baptist minister faced charges that he’d seduced one of his married congregants, now embroiled in a very public divorce. Adding to the shame were accusations that church deacons had tried to bribe the woman to remain silent about the affair.

The one national headline to break through involved questionable leases to the Navy’s oil reserves to private interests, granted by the late President Warren G. Harding’s Secretary of the Interior, in an area of Wyoming called Teapot Dome.

The nation marked the fourth anniversary of national prohibition on January 17. The Chicago Crime Commission received a report from its director that proclaimed Chicago one of the safest cities in the country. The Inquiring Reporter asked four Chicagoans encountered at 11 South Dearborn if prohibition had been a success; the responses from a bond salesman, two homemakers, and another salesman were divided, with a fireman saying it was too early to say one way or the other.

Police officer John Mulcahy, found culpable for the boozed-fueled New Year’s Day fatal shooting of cabaret employee Jenny Plarr, had the verdict of a second grand jury inquest voided by a judge who’d deemed the proceeding illegal.

An association of Chicago women’s clubs debated whether or not to recommend that the films of Mabel Normand, embroiled in her own boozy scandal in Hollywood, be banned, but decided to invite the actress to speak before them and defend herself; Normand agreed to visit Chicago as soon as she was able.

A photograph of Kate L. Butler, from Dorchester, MA, appeared in the newspaper with a caption calling her “Edison” for having won, with one other entrant, a contest to coin a new word to describe Prohibition violators like Mulcahy and Normand: scofflaw.

Had he been alive, Benjamin Franklin would have turned 218 this week. In an attic in New Jersey, his printshop “work book” or ledger from the last decades of the eighteenth century, believed lost to history, was discovered. In Chicago ten men with the first name “Benjamin” and middle name “Franklin” held a luncheon at the Union League Club, followed by a laying of a wreath at the base of the diplomat and inventor’s statue in Lincoln Park.

It was a week of innovation to make Franklin proud. In France, a flying machine, the helicopter, stayed airborne at 15 feet for over eight minutes. In the United States, Radio Corporation of America’s David Sarnoff sent a message asking about the weather 14,000 miles by radio from San Francisco to a station in Tomioka, Japan in 105 seconds. It was the first time a radio signal had traveled such a distance successfully. Sarnoff predicted a future of global connection through “radio television” where “Americans sitting in their homes not only will hear concerts, plays, and operas being broadcast in the great cities of this country but that the farmer may some day hear and see, by radio, on the farm, what is going on in Paris, London, or some other foreign city.”

Closer to home, the South Park Commissioners had met and agreed to accept a gift of $250,000 for the erection of a fountain, “equipped with colored electric lights,” the following summer in Grant Park. The gift of the fountain was made in the memory of her late brother Clarence by Kate Buckingham.

Week Four: January 20-January 26, 1924

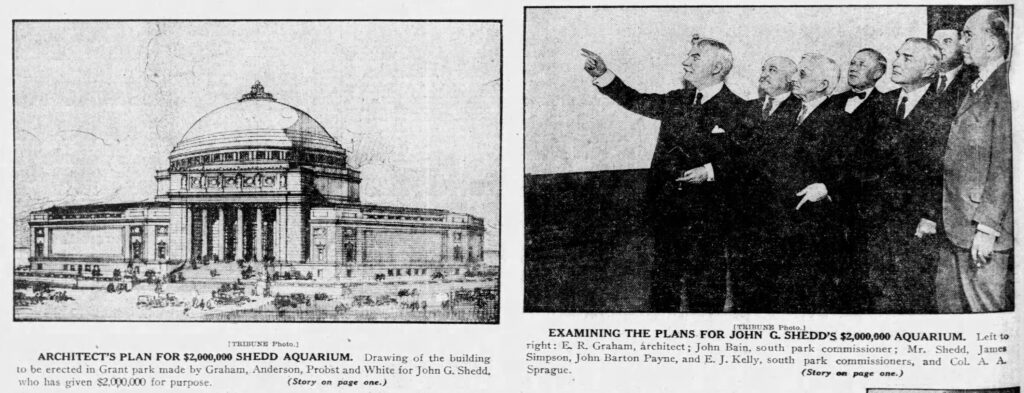

In the fourth week of 1924 during a dinner at the offices of the architectural firm Graham, Anderson, Probst, & White, the chairman of the board of directors of Marshall Field & Co., John G. Shedd, announced a $2 million gift to the South Park Board of Commissioners to support the building of an aquarium adjacent to the Field Museum of Natural History. The aquarium, to be designed by the firm hosting the dinner, would be “two and one-half times as large as New York’s” and be the “equal of the best in Europe, which is said to be that at Naples.”

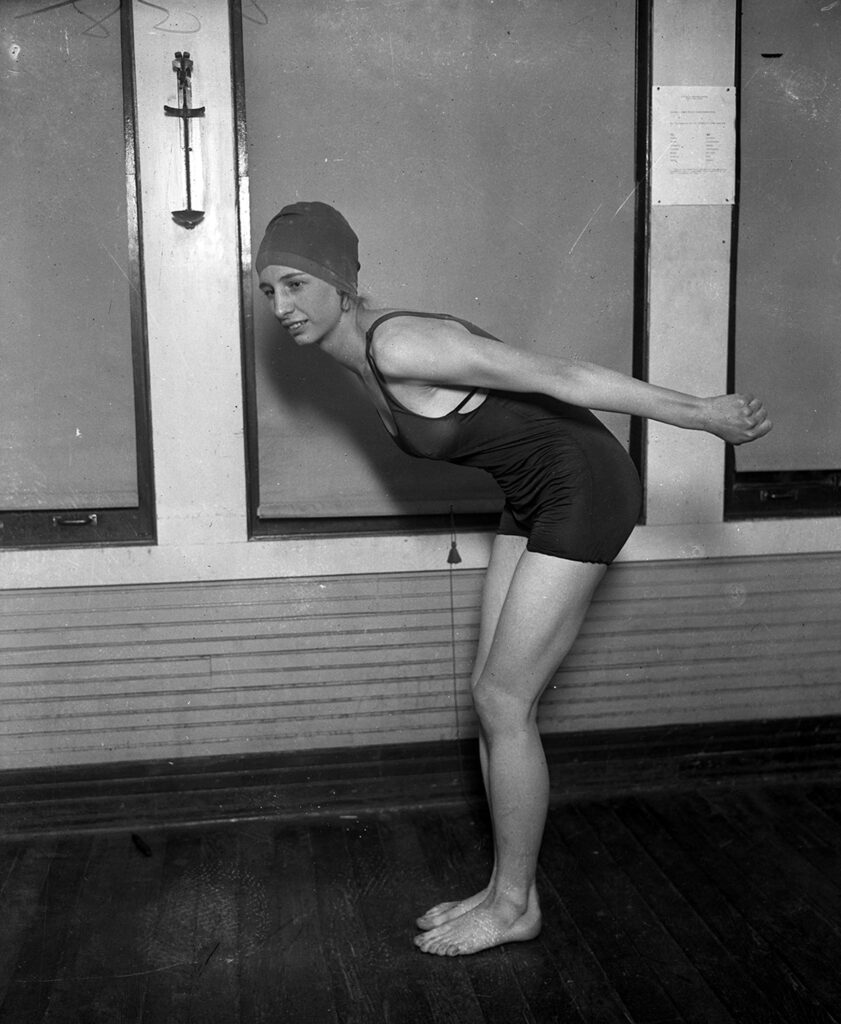

An aquatic accomplishment of a different kind had occurred earlier in the week in Fort Wayne, Indiana, when Illinois Athletic Club swimmers Sybil Bauer and Johnny Weissmuller set new world records in the 100-yard backstroke and 400-yard freestyle respectively. Back in Chicago, amid brutally cold conditions, 15,000 turned out to watch 600 skaters participate in the Chicago Tribune’s Silver Skates Derby held on the lagoon in Garfield Park.

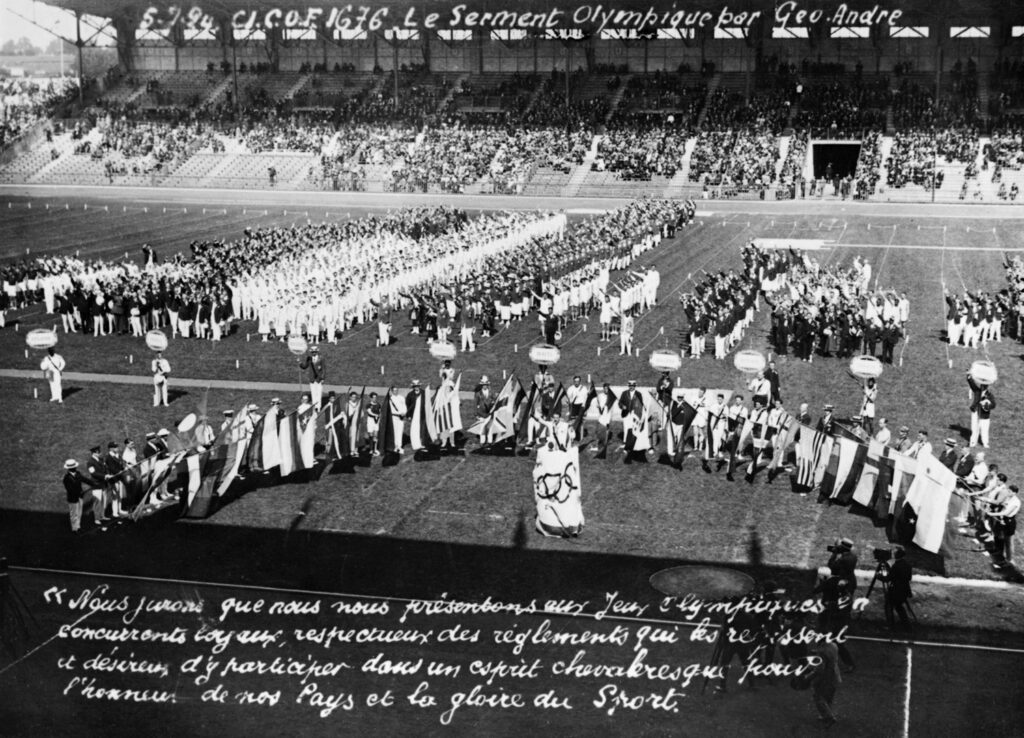

Over in Chamonix, France, at the base of Mont Blanc, what became regarded as the first Winter Olympic Games opened with 16 nations participating. The American team sang “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad” at the opening ceremonies, and American speed skater Charles Jewtraw won the first gold medal.

The most gripping athletic contest of the week, for locals at least, unfolded over three days in Orchestra Hall, when Willie Hoppe of New York faced Jake Schaeffer of San Francisco to determine who would be the international 18.2 balkline billiard champion. A clearly exhausted Hoppe prevailed on day three, retaining his title.

Rivalries of a more serious nature unfolded across the world in the fourth week of 1924. In Moscow, thousands waited in the cold for a chance to view the body of V.I. Lenin, who had died on the 21st, while Tribune foreign correspondent John Clayton reported on speculation as to who would assume control of the Russian state, Leon Trotsky or Joseph Stalin.

In Georgia, old divisions appeared etched in stone when artist Gutzon Borglum unveiled his head of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, part of an immense sculptural relief on Stone Mountain. At the unveiling, timed to coincide with Lee’s birthday, Emory University’s Plato Durham delivered an address in which he proclaimed that the “man who calls Lee a traitor is doubly damned.”

The never-ending conflict between capital and labor took an unexpected turn when Meyer Perlstein of the International Garment Worker’s union admitted challenges organizing women workers in non-union shops; the manufacturers, he claimed, had taken to hiring “Sheiks”—that is, handsome cads—to take the women to dances on the nights of organizing meetings and, between acts of romance, spread anti-union propaganda.

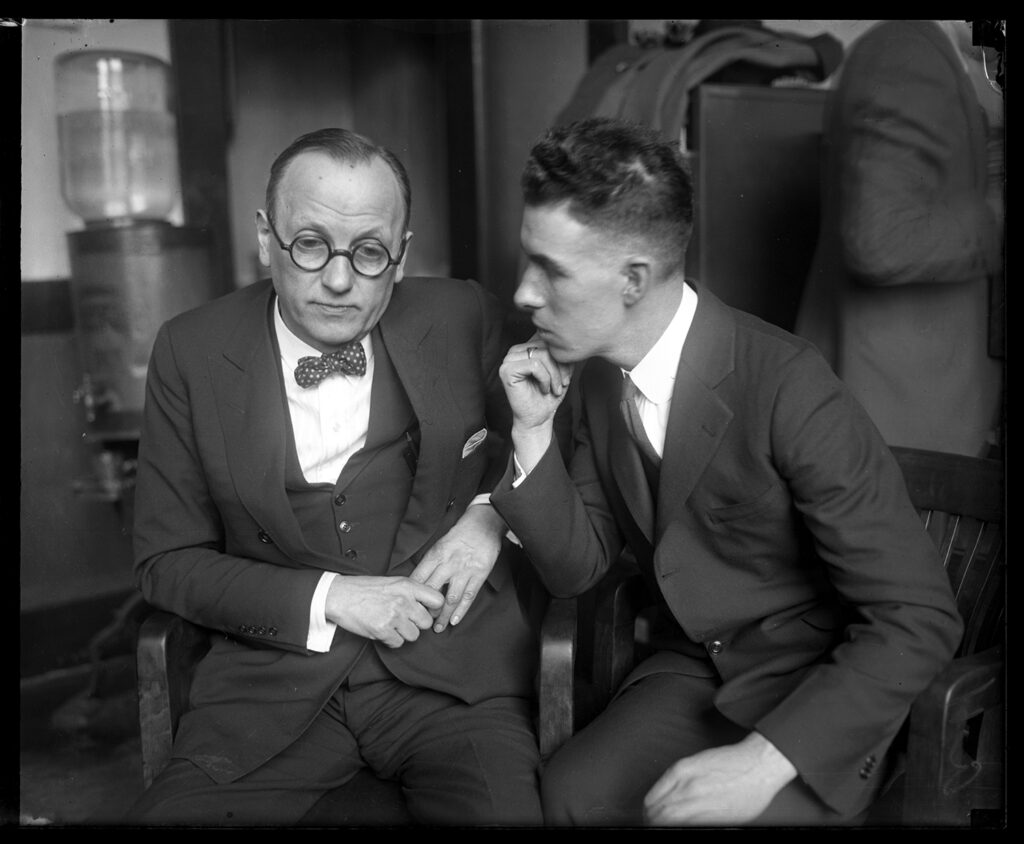

Two “sharps” were shot when stepping out of the lobby of the La Salle Theater after catching a first night show at the popular venue in the Loop with their wives. Moments after the four shots rang out, chaos erupted among the estimated crowd of 1,000 leaving the theater, making it difficult for police to determine who had downed brothers Davy and Max Miller, West Side gamblers and grifters. Within days, however, they had apprehended the most likely suspects, a north side florist and former singing waiter named Dean O’Banion and his associate, the notorious “perfume burglar,” Earl Weiss.

Week Five: January 27-February 2, 1924

A thick fog covered the city near the end of the fifth week of 1924, leading to calamity. There were numerous automobile accidents. Illinois Central and L trains collided. The worst occurred on the Ravenswood elevated line where one train struck the rear of another, leaving 40 passengers with injuries, although most were superficial.

Earlier that week, a metaphorical fog lifted in the strange case of Warren J. Lincoln, lawyer and floriculturist from Aurora, a man believed to have been killed by his wife and brother-in-law, who turned up alive, only to disappear again, and, finally, was apprehended when attempting to pick up funds mailed to his missing, presumably murderous, wife. Interrogated by his longtime friend, Aurora’s chief of police, Lincoln changed his story yet again, finally admitting he had murdered his wife and brother-in-law. He led investigators to a city dump along the Fox River, not far from his home and greenhouse, and there, wrapped in burlap and encased in a 18”x 36” block of cement, were the severed heads of his wife and brother-in-law. Lincoln said he’d come upon them having sex and in a fit of rage shot both fatally, but the chief of police believed that the brother-in-law’s money served as the true motive. The remainder of the two bodies, Lincoln confessed, he burned in the greenhouse furnace.

The same day the Tribune reported Lincoln’s confession, it announced the opening of the twenty-fourth annual National Auto Show, which would run from Monday through Saturday of the week, from 10am to 10:39pm daily. A record number of attendees turned out to see 500 new automobiles, many featuring such innovations as four-wheel brakes and balloon tires, with the show spread across the Drake Hotel, the 131st Infantry Armory, and the Coliseum, the latter full of decorative art “reminiscent of the Louis XIII and Louis XIV periods,” emphasizing the automobile’s place as a true status symbol.

Outside Chicago and around the world, Prince Hirohito of Japan wed Nagano Kuni, while the musical comedy star De Wolfe Hopper, after being caught in the company of a chorus girl, was divorced by his fifth wife, Elda, known on the stage as Hedda Hopper. In Italy, Benito Mussolini purchased for the state the tomb of Virgil, which had been on privately owned land, and kicked off the general election by urging a crowd of thousands to turn out at the polls to oust an oppositional parliament, “For our Fatherland, for Fascism.” He declared himself and fellow Black Shirts “ready to kill or die” to secure electoral victory.

The presidential aspirations of Democrat William McAdoo, former Secretary of the Treasury and son-in-law of Woodrow Wilson, were challenged when his name was linked to the expanding Teapot Dome scandal; however, McAdoo, an attorney, in a forceful response to Congressional investigators delivered from his law office in Los Angeles, stated he had represented oil interests only in Mexico and never had anything to do with leases on federal land in Wyoming.

Princeton University, where Wilson had served as president, turned up in the news, when five of its faculty were asked to name the six most significant words in the English language. Four of the five gave a response similar to J.D. Spaeth from the English Department—”Liberty, loyalty, sympathy, justice, intelligence, character”—but Henry Van Dyke recognized utility with his list of “a, the, is, no, yes, do.”

In Washington, Wilson wasn’t doing that well, but his attending physician assured the public that he “did not consider the former President’s illness serious.”

Week Six: February 3-February 9, 1924

Deaths of note bookended the sixth week of 1924. The passing on February 3 of Woodrow Wilson, the former President of the United States, filled the front page of the Sunday edition of the Tribune. In his home in Washington D.C., with his wife and eldest daughter at his side, lying in a replica of the bed Lincoln had used in the White House, Wilson slipped into a coma and died quietly, his dream of the United States joining the League of Nations unrealized.

On Friday of that week, halfway across the country, in Carson City, the state of Nevada executed a human being by exposure to lethal gas—the first use of this method in the United States. The cyanide had to be brought over from California, where it was used to fumigate crops, and was tested on a cat in a chamber in the prison’s butcher shop that could be sealed safely. Satisfied with the test, prison and medical officials moved on to executing Gee Jon. In 1921 he had traveled from San Francisco to a small town in Nevada to murder an elderly member of a rival gang. A terrified Gee was strapped to a chair in the chamber; within moments of being exposed to the gas, his head slumped forward, bobbing up and down for several minutes before going still. Witnesses had to be evacuated out of fear that the gas was leaking from the chamber. Despite the speed and apparent humaneness of lethal gas, the prison’s warden stated that he still preferred the use of a firing squad in executions.

Between these moments of quiet passing, the city of Chicago continued on with the conflict and calamity that had defined so much of the beginning of the year. The newspaper reported on a dance thrown by the Teamsters union at Carmen’s Hall, near Van Buren and Ashland, which had devolved into a riot in the early hours of Sunday, leaving one dead and twelve recovering from gunshot wounds. Winter reasserted itself with a storm of snow, rain, and sleet that led to one streetcar derailing and two others colliding while numerous trains stalled on the tracks outside the city. All were aided not by telegraph wires, downed by fierce winds, but by the radio, which effortlessly transmitted information about the trapped train passengers to rescuers and stories about the storm to newspapers across the country. Not wanting to miss reporting a moment, the Tribune turned to WJAZ, a station owned by Zenith and broadcasting out of the Edgewater Beach Hotel, to alert cities to the west of what was happening in Chicago.

The storm did not deter attendance at a revival of a motion picture beloved by the late Woodrow Wilson, The Birth of the Nation. What did disrupt the screening at the Auditorium was a judge, intentionally seated in the audience, who determined that the film violated a state statute, passed in 1917, that barred the “showing of pictures which tend to engender race or class hatred.” Police shut down the showing of the film, repeated the effort on the following evening, and then stood aside and let the film play while an injunction worked its way through the courts.

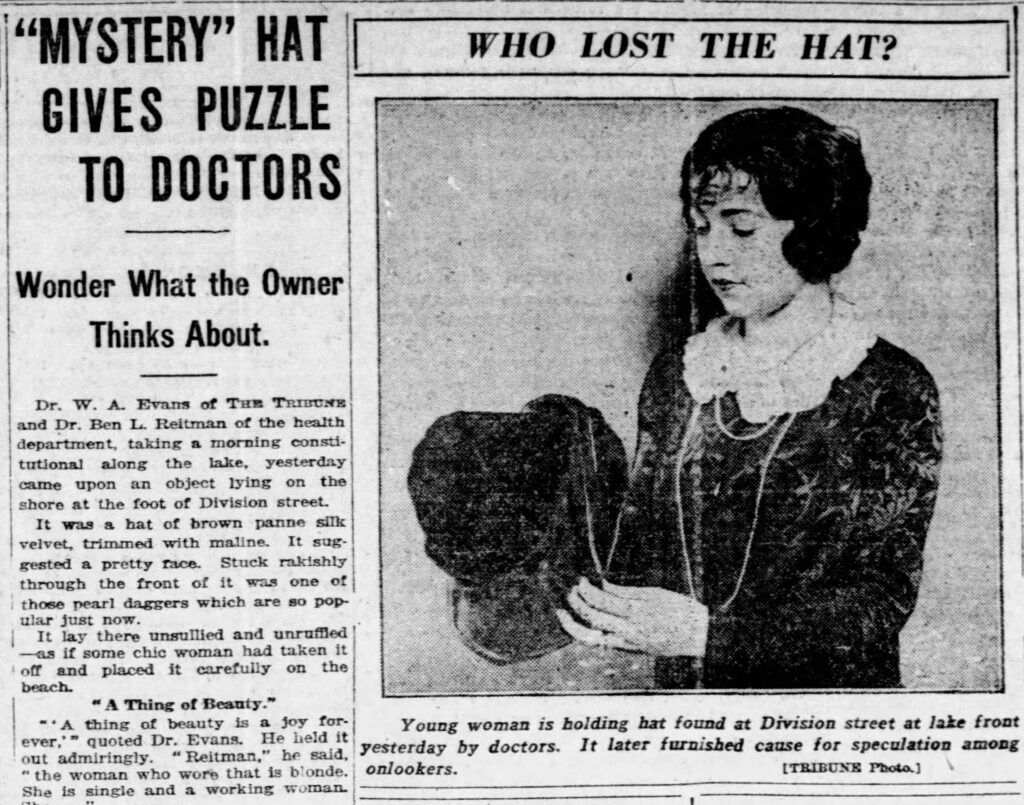

Amid all this, readers of the Tribune became privy to a minor mystery when it was reported that the paper’s health columnist, Dr. W.A. Evans, while walking along the lakeshore at Division Street with Dr. Ben Reitman, physician to the hobos and denizen of the Dil Pickle Club, came across a woman’s brown velvet hat laying “unsullied and unruffled” on the sand. This discovery prompted the men to turn detective and use the qualities of the hat to determine the character of its owner.

Noting the pearl dagger pendant “rakishly” pinned to the front, Evans concluded she was a young, blonde, single, working woman. Perhaps not single but married, Reitman suggested, although he gave no reason for this conclusion. Had this woman walked into the lake and ended her life, as Evans deduced, or had the hat blown off her head while she rode on the top level of an open air motorbus, as Reitman maintained?

They brought the hat to the Tribune’s office where more speculations were made by journalists. A label on the lining led them all to the hat’s maker who in a phone call remembered the owner as being a rather nondescript woman.

Within a day, the mystery resolved itself when the owner, Mary Edna Cook, came forward, saying Reitman was correct, she had been on a bus, near the lake, when the hat blew off her head. She thought it lost forever. Cook worked as a secretary for the Sinclair Oil Company, in the news that week for its connection to the Teapot Dome scandal.

Week Seven: February 10-February 16, 1924

A baby fell into the snow and a child slipped under the ice in the seventh week of 1924.

Two-year-old James Novello tumbled off the upper porch of his family’s home but landed headfirst into a pile of snow. When his mother found him, he was kicking his feet in the air.

Marie Schram had a more harrowing experience when the twelve-year-old, out on the ice covering a drainage canal in Evanston, fell through. The screams of her schoolmates who’d dared her to go there attracted the attention of a passing delivery truck driver for Marshall Field, Robert Phil. He leapt from his vehicle with a length of rope in hand. Fastening the rope around an object found on the shore, Phil, an experienced swimmer, edged out onto the ice. The rope wasn’t long enough to reach the open water, so he slipped free of it and dove in to retrieve the struggling Marie.

Several times she went down, and Phil followed, before finally gaining a good grip on her and treading back to the edge of the ice and the end of the rope. By this time, others had gathered who helped pull the two up and out of the canal. Marie was wrapped in blankets and placed in the back of a limousine, which sped off toward her home. A cold and tired Phil remained alone at the site until a passing motorist picked him up. The Tribune, learning of the incident, recommended Phil for a Carnegie Medal for heroism.

The long certainty of the past offset the precariousness of the present in the seventh week of 1924. Chicago and the nation observed the 115th anniversary of the birth of Abraham Lincoln. At the city’s historical society, Addison Proctor, 86, the sole surviving delegate to the 1860 Republican convention, told the “true story of Lincoln’s nomination for the presidency.”

Proctor had come to the convention in Chicago from Kansas intending to support New York’s William Seward. Party leaders, however, come to believe that the “border states—between the north and the south—held the balance of power. They kept telling everyone they wanted a nominee born among them—one who understood them.” That led to the nomination of the Kentucky-born Lincoln. After the talk, visitors to the historical society had the opportunity to view the gray shawl Lincoln wore in New York when he made his famous Cooper Union speech, a whittling knife, a lock of hair, and other artifacts.

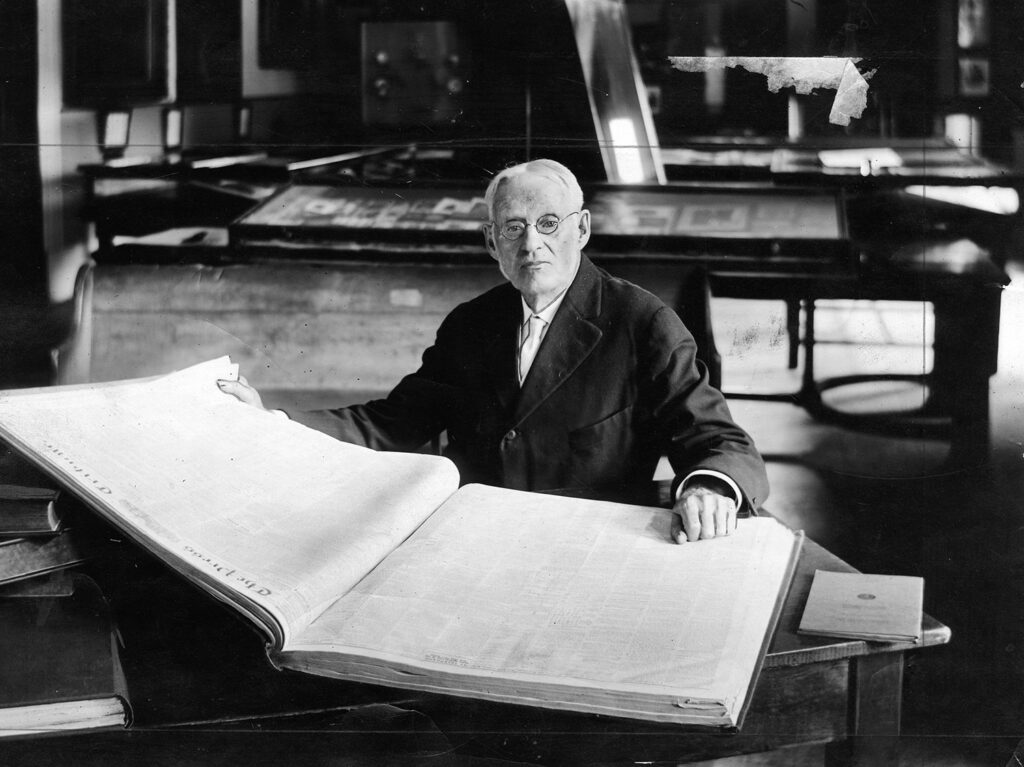

In Egypt the University of Chicago’s James H. Breasted was among those who witnessed the truth of a much deeper past revealed. Outside Luxor, in the Valley of the Kings, within pharaoh Tutankhamun’s tomb, a story millennia in the the making neared its end when a system of pulleys lifted up the heavy pink sandstone lid of the inner sarcophagus holding the mummy case containing the ancient ruler’s body. The first to look inside was archaeologist Howard Carter, who had rediscovered the tomb in 1922. At first, he saw only shrouds of darkened linen, which he and a colleague began to slowly roll from the foot upward until they exposed a “gleaming, golden man.” Set within an exquisite mask that captured the “wistful, beautiful, boyish face” of Tutankhamun,”gleaming eyes of aragonite, strangely and eerily lifelike” gazed up at Carter and the others assembled there.

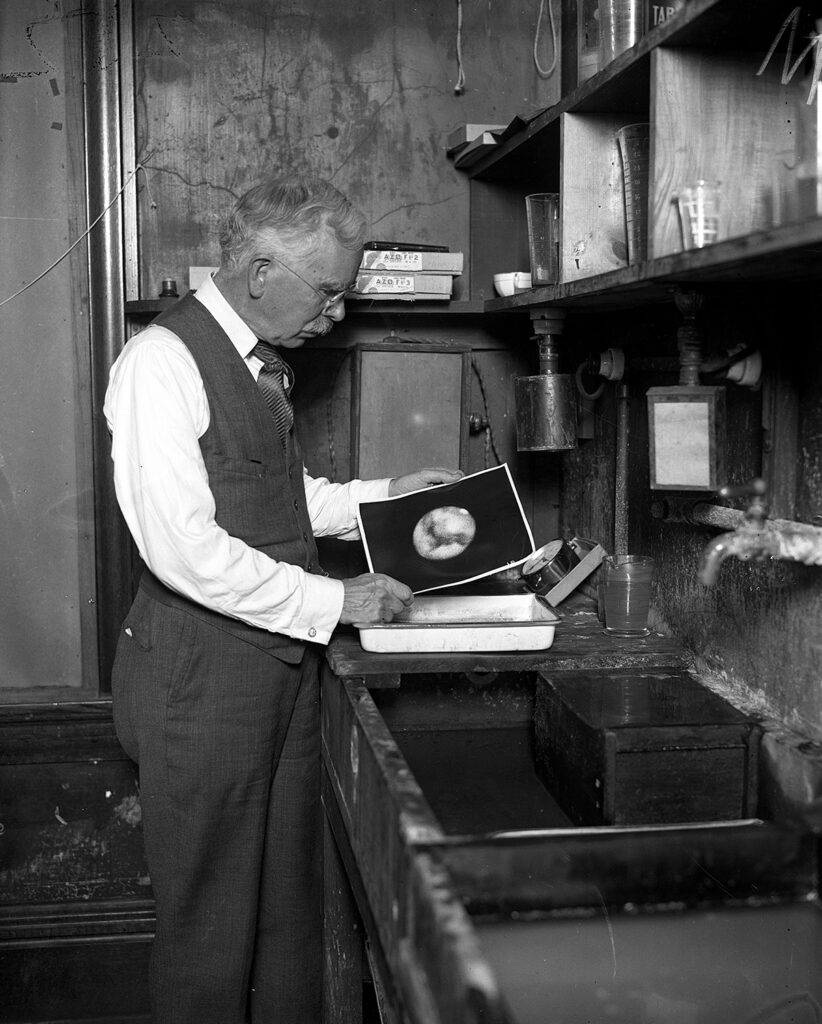

A relic of a different sort, capitalist inventor Thomas Edison, turned 77 in the seventh week of 1924. Interviewed in West Orange, New Jersey, where he lived and worked, Edison said he was “good for, say, ten years yet,” thought Calvin Coolidge would win the fall presidential election, considered radio the most important technological innovation of the year, and proclaimed that when oil and coal were exhausted as sources of energy, they’d be replaced by “(s)un, wind, tides, and vegetable growth.”

A part of the past many Chicagoan preferred to forget resurfaced when a jury awarded Joseph Jefferson “Shoeless Joe” Jackson—former White Sox baseball player disgraced by his believed involvement in the crooked 1919 World Series and banned from the sport for life—the pay that was owed to him for the 1920 season. Outraged by the verdict and citing perceived perjury in some of the testimony, the trial judge set it aside and dismissed the case. Jackson’s attorney planned to appeal, citing the verdict as the first step in the player’s “ultimate return to organized baseball.”

For those still involved in the sport, its seasonal return was fast approaching. On Saturday, thirteen pitchers, three catchers, and four infielders from the Chicago Cubs boarded a train bound for Los Angeles. From there, they’d get on a boat to Catalina Island, owned by chewing gum maker and the club’s owner William Wrigley Jr., for the start of spring training.

Week Eight: February 17-February 23, 1924

The Year of the Rat started with a bang in the eighth week of 1924. In “old Chinatown in Clark Street and the new one in 22nd street,” strings of firecrackers suspended from second- and third-story windows erupted in streets “ablaze with lights”as the community welcomed the New Year. All debts must be paid, according to resident Frank Moy, so that one starts the New Year with a clean slate.

In Chinese mythology, the rat is considered a clever creature, and Chicago’s criminal underclass demonstrated this quality during the course of the week. On the eve of Chinese New Year, the police raided the headquarters of an underground lottery game in the Loop. Frank Averitt, the organizer of the operation, had a unique source for his winning numbers, the US Weather Bureau. “The temperature report at certain specified hours of the day is said to have provided the digits for the lottery figures,” the Tribune reported.

A few days later a cashier at the People’s Trust and Savings Bank on north Michigan Avenue returned to his cage mere minutes after leaving it only to discover several notes and certificates scattered around a drawer he’d left open. Some of the notes were covered in a sticky substance and gave off a hint of spearmint, leading investigators to conclude that some thieves had used a penny pack of gum, attached to the end of a stick, to reach through the bars of the cage and lift up and out what was determined to be $50,000 worth of certificates. A similar crime had occurred a month prior at a bank in Indianapolis, suggesting the start of a spree. Unfortunately for the gum bandits what they plucked, while valuable, was difficult to redeem, as they were all “United States certificates of indebtedness.”

The value of a historical artifact came under debate at an auction in Philadelphia. Did the “Mr. Douglas,” who successfully bid on the coat worn by Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theater on the night the president was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth, receive the genuine article? Not so according to the the Chicago Historical Society who claimed to have the coat as part of its collection. Frank G. Logan, who gifted the coat to the Society, said he had the documents to prove its authenticity, while the auctioneers in Philadelphia said they had their own sources of their coat’s provenance.

Logan contributed a significant sum to keeping another object of historical importance in Chicago this week. A portrait of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart, on loan and on display at the Art Institute of Chicago, was available for purchase if sufficient funds could be raised. The Chicago Herald-Examiner launched a campaign to keep it in Chicago, which was soon joined by the city’s other morning newspaper, the Tribune.

Someone who was not first in the hearts of his countrymen—and who, not surprisingly, turned up at the beginning of the Year of the Rat—was the former Mayor of Chicago, William Hale “Big Bill” Thompson. His Honor, along with the former city comptroller and the head of the Lincoln Park Commission, put forward the funds to incorporate the South Sea Research Company, which planned to dispatch on July 4 an expedition to discover and document “acrobatic fish,” the kind that can “climb trees, live on land, and jump three feet to catch a grasshopper.”

A bit of the wild came closer to home when three young lions broke free of their cage on a baggage car headed from Minnehaha, Minnesota to Sellers, Maryland, where the animals’ owner, a circus, wintered. By the time the train reached Chicago, the lions had taken full possession of the baggage car, but a “Lincoln Park trainer” succeeded in coaxing them back behind the bars.

Week Nine: February 24-March 1, 1924

(Chicago Tribune historical photo)

In the ninth week of 1924, predators of all sizes stalked Chicago and the world. Driving back to the city from Tomahawk, Wisconsin, Thomas Smith claimed to have been pursued by five large gray wolves near Milwaukee and Devon avenues, making him the “latest victim of the great wolf scare in Cook county.” Earlier in the year, a pack of twenty-four wolves sighted along the Elgin road were determined to be friendly “German police dogs,” belonging to an attorney who lived nearby. Said Smith of his encounter, “I have been in wolf country for a week and never saw a wolf.”

Women were on the prowl across the city on February 29 if a Tribune article with the title “Watch Your Step, Men; They’re After You Today” is to be believed. The article referenced an old tradition allowing women to propose to “unattached men” on Leap Day. Men, as usual, seemed to be the ones doing the most pursuing. Joseph “Yellow Kid” Weil, known as being “without peer as a con man,” found himself accused in a divorce suit of having stolen the heart of Helen Carrozzo, the wife of a former Street Sweepers Union president and known gangland associate. Weil admitted knowing of the man but said, “I’ve never seen nor met his wife. It’s the bunk.”

At a Polish dance hall in South Lawndale, a dispute between lovers didn’t look likely to reach the courts. Refused a dance from former fiancee Mary Mitas, Edward Kociza pulled out a revolver and shot her in the face before turning the gun on himself to the horror of the couples dancing around them. Both survived the shooting, although they were expected to die from their wounds. Kociza retained consciousness throughout the trip to the Bridewell infirmary where surgeons, having discovered the “bullet lodged at the base of his brain, marveled that death had not been instantaneous.”

The Vatican publication Osservatoro Romano would have placed the blame for this shooting and all “recent flagrant immorality” squarely upon popular dances such as the “shimmy” and “camel’s step.” In an article published that week, it warned of the dangers posed by these dances with their “imitation of animal movements.”

The Church itself came under attack at a trial for high treason that began in Munich in connection with the previous November’s failed insurrection there, the infamous “beer hall riot.” On trial were former Field Marshall Erich Ludendorff and the “leader of the Bavarian fascisti,” Adolph Hitler. The two veterans of the Great War contrasted in appearance and style, with Ludendorff composed and clad in a pressed blue suit and Hitler animated and wearing an old “black coat showing tinges of green and shiny areas on the back and sleeves.” Ludendorff spoke for both when he proclaimed, “We want a Germany free of Marxism, semitism, and papal influences.”

Similar sentiments found expression back in the United States but also ran into opposition. The Ku Klux Klan found its meeting at the Commercial Hotel in Waukesha, Wisconsin disrupted by “2,000 citizens” who objected to the group meeting there. The police and members of the American Legion had to hold back the protestors so that Klan members and their sympathizers could safely flee.

Back in Chicago, during a talk at the University Club, Dr. William Paxton Burris, “dean of the college of teachers of the University of Cincinnati,” called upon the National Education Association to proclaim the Klan “100 per cent American” in exchange for the “invisible empire” supporting a congressional bill that called for establishing a cabinet-level department of education.

Another bill slowly moving through Congress would significantly alter the nation’s immigration laws. The Tribune warned, however, that the bill had one glaring omission: it did not take into account illegal immigration across the Canadian and Mexican borders of the United States. In two editorials over successive days, the newspaper drew attention to the number of Mexican immigrants who were coming to work and live in Chicago, having established their own neighborhoods near the new Chinatown, along 23rd and 24th Streets, and between Peoria and Newberry Avenues. While acknowledging the critical contributions made by this community to the city’s economy, the paper nonetheless fretted about unchecked immigration and the inability of legislation to address it: “The Mexican border is long enough and wild enough and there are enough ports of entry, into Mexico, to nullify any restrictive system in time, unless it is corked up.”

Week Ten: March 2-March 8, 1924

Thoughts filled the ether at the start of the tenth week of 1924. Three college psychologists sent out their thoughts over the airwaves from WJAZ, the radio station at the Edgewater Beach Hotel, in the largest test of telepathy in history. In a series of twelve three-minute tests, thousands of listeners at home were asked to receive and record thought projections of, among other things, a number from 1 to 1,000, an animal, and a piece of food consumed by one of the psychologists at the station. All results were to be submitted by midweek.

Similar mysteries of the heart and mind filled the pages of the Tribune during that week. Two former reporters, John Seymour and Thyra Samter Winslow, announced that after twelve years of a happy marriage, they were separating—not getting a divorce but rather taking a one-year vacation from matrimony. They planned to go together to Europe once the year was up. Explained Thyra, “For twelve years we have been together so much that we are afraid of losing our individuality.”

While the Winslows were putting their love on hiatus, another couple was just getting started. The previous fall, Erlean Berry had found herself temporarily overwhelmed by the rush of traffic in the middle of State Street, near Madison, the “world’s busiest corner.” Standing still amid the streetcars, taxicabs, and pedestrians passing around her, Erlean was awakened from her stupor by a shrill whistle blown by Officer Edward Schimmel. Expecting to harangue her for jaywalking, the officer instead found himself smitten when she looked into his eyes and smiled. A romance took its first step as he led her across the street. In the tenth week of 1924, they married.

Such tenderness was intended to be absent from the Christ Brotherhood religion, founded by one Adam Thomasson and based in a boarding house on Clark Street. The dozen followers of Thomasson abstained from sex, meat, and, money—the latter in the sense that they gave everything they earned over to their god incarnate. Apparently, Thomasson didn’t practice what he preached, as he was hauled before a judge, accused by disillusioned followers of propositioning some of them for sexual favors and using the church’s funds to purchase real estate in Florida. He did, it seems, practice vegetarianism. “All we get is raw carrots three times a day,” said one of the apostates, who deemed the lack of variety in the diet the worst offense.

Such restrictions would have protected the Christ Brotherhood members from falling afoul of some bad eggs—144,000 of them that went missing from a wholesale grocer. The eggs had been identified as “decomposed” by government inspectors upon their arrival in Chicago from the Ozarks. Intended for industrial use in a tannery, the eggs instead disappeared. Assistant District Attorney Mary D. Bailey brought suit against the grocer, who admitted to selling the bad eggs but wouldn’t name the buyer.

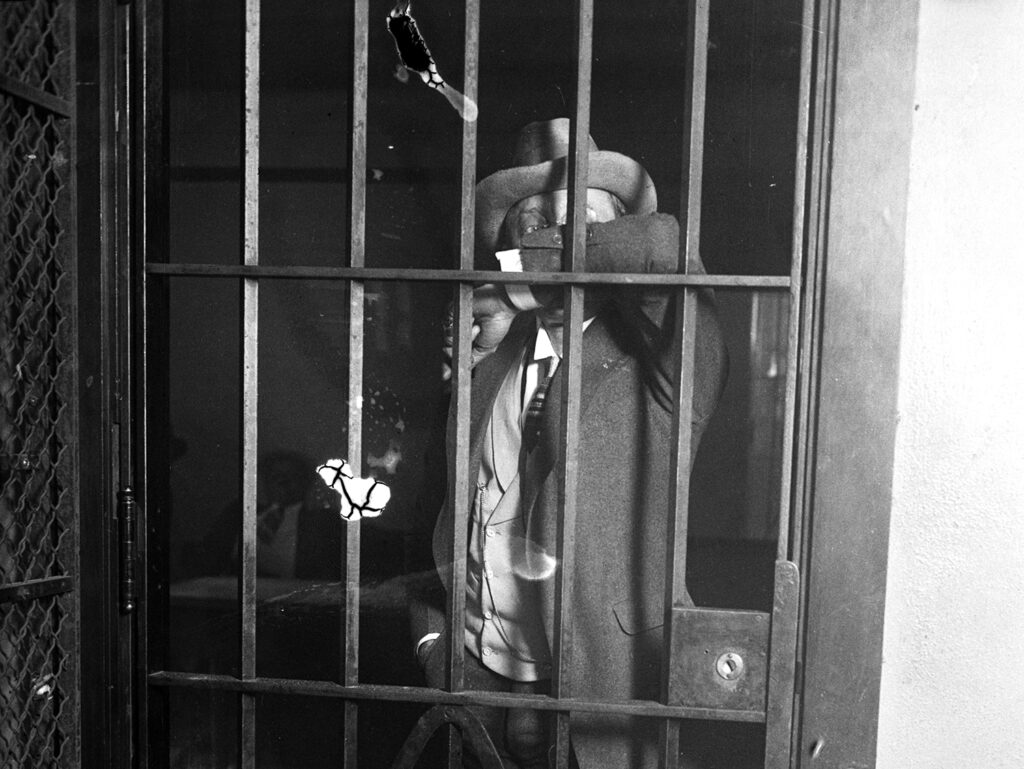

Growing frustrated with the lack of progress in the investigation of the murder of underworld figure John Duffy and his common law wife two weeks prior, State’s Attorney Robert E. Crowe decided to round up all of the city’s bad eggs, the human kind. These included several high-ranking hoods who were “nearing the millionaire stage through the peddling of contraband liquor,” such as Dean O’Banion, Earl Weiss, John Torrio, and one Al Brown, who obscured the lower half of his face with a newspaper when his photograph was taken by the Tribune.

Brown’s face would become well-known soon enough. What was known by Wednesday was that thoughts apparently couldn’t be transmitted over the radio. Four thousand WJAZ listeners mailed in responses to Sunday’s telepathy test. Out of that pool, 150 were selected and reviewed. No one identified the correct number, 664, although several, curiously, put down 994 and 499. No one picked a walrus, with a zebra and an elephant being the most popular choices. And no one could say that one of the psychologists had munched on a small beet.

Week Eleven: March 9-March 15, 1924

The ball got rolling in the eleventh week of 1924. The largest ball in the world, a “huge inflated sphere covered with red, white and blue leather,” set off from Chicago on a “tour of the country.” Destinations included Detroit, Cleveland, Buffalo, Albany, Philadelphia, New York, Washington D.C., Atlanta, New Orleans, Fort Worth, Los Angeles, Salt Lake City, Denver, Kansas City, and then Chicago again to complete the circuit. Pushing the ball were Boy Scouts, American Legionnaires, and members of other patriotic organizations, all in support of “citizens’ military training camps” run by the government. It was estimated the complete trip would take eighteen months.

As the ball moved forward, readers of the Tribune were invited to reflect back on past events. In Chicago, stories from the first weeks of the year, buried in the interior pages, reached their seeming conclusion. Officer John Mulcahy who had fatally shot cabaret employee Jenny Plarr on New Year’s Day was convicted of manslaughter and faced a sentence of one year to life. Edward Kocizca, who had fatally shot Mary Mitas at a Polish dance hall before turning the gun on himself on February 24, died of the gunshot wound to his head. Promoters of The Birth of the Nation won the right to screen the film at the Auditorium, which had been raided and shut down by the police during the week of February 3, after a jury determined it did not promote racial animus.

A more distant past also came to mind during the week. The St. John Baptist Church announced plans to honor Booker T. Washington, who had passed away in 1915, with a new social center to be built at Grand Boulevard and 36th Street. Originally from Alabama, the Reverend F.A. McCoo, pastor of St. John’s, had been a friend of Washington’s. The center was to have a statue of the educator outside the first floor assembly hall, along with offices for doctors and dentists on the second floor, a gymnasium on the third, and a dormitory on the fourth.

Harry K. Thaw, the millionaire who had murdered architect Stanford White in 1906 and then pled temporary insanity, received the right to a new trial to determine if he was sane enough to reenter society.

Inventor Nikola Tesla emerged from seclusion with the announcement that he’d perfected a “system of transmitting power without wires.” The system involved an “electrical generator which delivers its energy into the earth, whence it can be unlocked”and be “transmitted over wide stretches.”More ominously, the energy could be concentrated “in a beam” to “explode distant stores of explosives, in arenas and warships.”

Radio waves were put to a more immediate use when a poll of WJAZ listeners was conducted to gauge support of modifying the Volstead Act, the “first radio poll ever taken on the prohibition question.” Listeners favored modifying the act 27,120 to 10,071. Responses came from across the country and Canada, with the largest concentration of “wets” residing in the city.

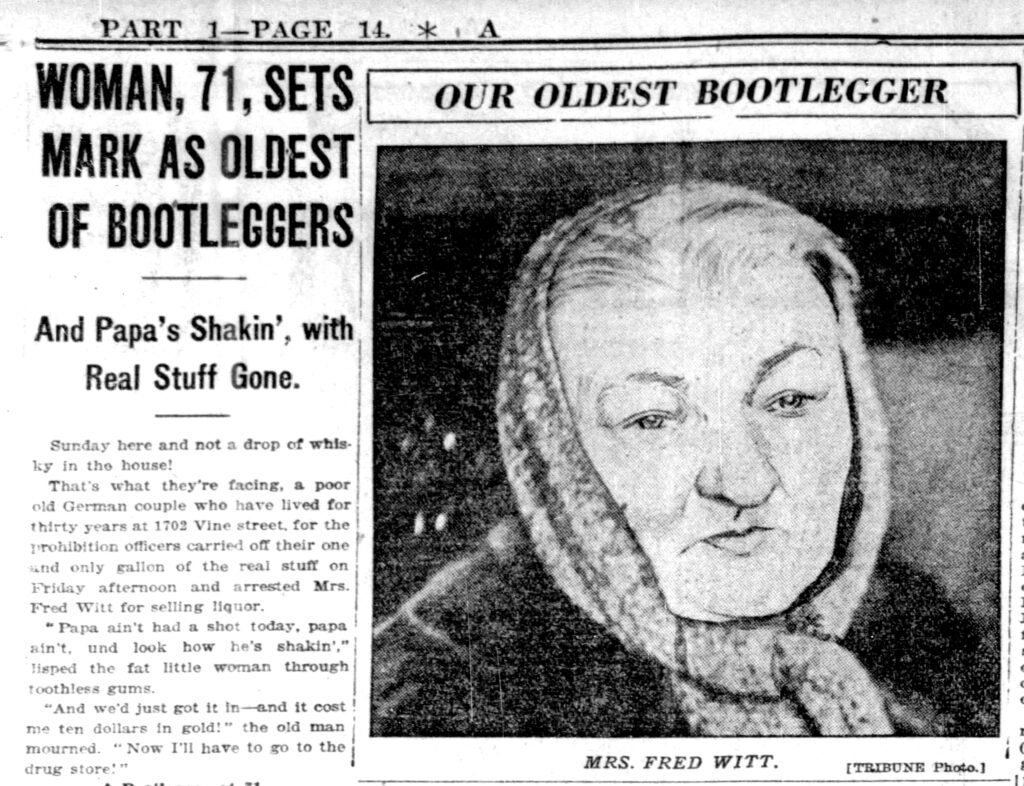

Law enforcement, however, remained indifferent to public sentiment. Arrested that week was Mrs. Fred Witt, Chicago’s “oldest woman bootlegger”at the age of 71, who had resold some of her prescribed weekly medicinal whisky allotment to three young men later apprehended for speeding. The young men would get probation, it was predicted, while the nearly destitute Mrs. Witt would be issued a $200 fine.

After three years of failed pursuit, authorities finally nabbed the “gray wolf of Sheridan Road,” so-called because of the bootlegger’s ability to elude capture in his sleek gray automobile and his list of affluent clients in Evanston, Highland Park, Lake Forest, and elsewhere along the North Shore. The “wolf,”it turns out, was a “squat little German chemist,” Otto Von Bachelle, who made his own hooch at his residence in the 1600 block of Wells and merely convinced the well-off they were getting the good stuff.

Criminals of a younger age no doubt trembled at the news that Chicago was organizing a force of 600 “Junior Police” to patrol the city’s fifty-five playgrounds. The majority were high school students and members of the ROTC. Patrolmen were to receive silver badges, and officers would receive bronze badges, bestowed upon them by Chief of Police Morgan Collins at the formal swearing in ceremony scheduled for early May. The new force would “minimize the dangers to which many teachers have been exposed at the hands of neighborhood gangs” and “attacks of rowdies upon school children will be eliminated.”

One threat the Junior Police couldn’t address was the invisible spread of disease. Fortunately, Chicago had health commissioner Herman N. Bundesen—who’d also made a citizens arrest of a truck driver in violation of the city’s “malicious noisemaking” ordinance that week—to respond swiftly to an outbreak of smallpox among students at Trumbull, Brown, Franklin, and Emerson schools. Unvaccinated students were ordered to remain at home to prevent the outbreak from becoming an epidemic.

Week Twelve: March 16-March 22, 1924

In the twelfth week of 1924, the first day of spring, March 20, brought snow. “At 3:20 o’clock the air was filled with white flakes which C.A. Donnel, weather forecaster for the Chicago district, readily identified as snow,” observed the Tribune. “A half gale made the storm take on the aspects of a blizzard.”

The week had gotten off to a blustery start. The Inquiring Reporter had asked five Chicagoans, “Why are people less agreeable on Monday than other days of the week?” Among the responses, Joseph Cerveny, whose profession was listed as “bread maker,” provided the most succinct: “I suppose because they have a week of hard work ahead of them, and maybe not too much pay for it. The fun’s all over and for six long days they have little to look forward to except monotonous work.”

“Monotonous” was not how one would describe a meeting of the city council’s finance committee as first reported on Sunday. Full-on fisticuffs broke out between Aldermen John H. Lyle and U.S. Schwartz as the two disagreed over whom should report on the law department’s budget needs. For three minutes the two brawled while several of their colleagues sustained injuries attempting to separate them. Having received some bruises and lacerations, the two ultimately reached an accord and left City Hall for dinner arm-in-arm.

The brawl preceded the finance committee approving the largest annual budget, at $46,609,700.00, in the city’s history. Alderman Lyle, the “lone dissenter,” vowed to claw back some of the expenditures on city worker salaries before the entire council voted on the budget.

Politics abroad was no calmer. Voters went to the polls in the Westminster district of London to fill a seat in Parliament. Running to represent the wealthy area were Conservative candidate Otto Nicholson, Liberal candidate Scott Duckers, Labor candidate Fenner Brockway and former Liberal MP turned “independent anti-Socialist” Winston Churchill. At the close of the day, Brockway and Churchill appeared to be the favored among the four. “The election is especially interesting,” the Tribune noted, “because, if Churchill, who is one of the most clever British politicians, wins he will become a recruit of the Conservative party, with a good chance of eventually securing the leadership and becoming prime minister.”

Another leader of a very different character was encouraging a very different practice of politics in Bombay. Recently released after two years of imprisonment for opposing British imperialism, Mahatma Gandhi gave an interview to the Tribune’s foreign correspondent Thomas Ryan. “Civil disobedience is always an advisable weapon when the government is not based on the will of the people,” said a visibly but not spiritually weakened Gandhi, “but it is practicable only when the masses are imbued with a spirit of nonviolence.”

In the interview, Gandhi voiced support for certain educational reforms and temperance in India. Back in Chicago, in the twelfth week of 1924, both were subjects for innovation. The Chicago Public Schools promoted its first fully “accredited branch” in the Cook County Jail, offering 120 incarcerated young men a chance at an education. Josephine Kumtinan, meanwhile, was arrested for fronting the most compact and mobile of speakeasies: “Underneath her long black coat she wore suspended from her neck by a stout cord a large copper tank, curved to fit comfortably over the body. This was equipped with a valve for measuring out a small quantity of liquor and also a couple of glasses.”

Week Thirteen: March 23-March 29, 1924

A fox took flight, and the President’s cat went missing in the thirteenth week of 1924. On Sunday on the southwest side, seventeen-year-old Milton Hons, accompanied by his three younger siblings, took his pet red fox Susie on a walk through the neighborhood. At one point Susie snatched the lead from Milton’s hand and sprinted toward freedom. The children gave chase, and soon others joined in, but the swift animal evaded them. It was not until Milton was able to flag down and commandeer a passing automobile that he overtook Susie, cornering her in an alley near 25th and Crawford Avenue, about ten blocks from where she’d escaped.

Standing pat rather than taking flight was Notre Dame football coach Knute Rockne. After being courted to take over Iowa’s squad, Rockne instead signed a ten-year contract with the Catholic university in South Bend, saying, “I will never leave Notre Dame as long as they wish to retain me.”

Also sticking around for awhile were the objects placed in the time capsule in the cornerstone of the new thirty-two-story Straus Building on Michigan Avenue, near Jackson Boulevard. Making up the contents of the capsule were “(f)ive phonograph records containing jazz music and the offerings of famous artists, a package of needles for the same, a strip of movie film, and Chicago newspapers bearing the March 25 date line—all representatives of civilization as it obtains in 1924.”

Time would tell if the contents of the capsule stay in place as long as the skull of the so-called “Los Angeles man” had—thousands of years, in fact. Recovered from a “vast glacial pond of oil in which skeletons of the giant sloth and the saber-toothed tiger” and other ancient creatures resided, the skull was “decidedly more primitive and more receding than that of the Neanderthal man.” Its discovery revived debate as to whether “man emerged from some lower state at one time and place on the earth or whether he evolved at various times and places.”

Something slightly less ancient was on display in Rome, as a phalanx of black-, red- and purple-robed men, led by Pope Pius XI, elevated George Mundelein, Archbishop of Chicago, to the College of Cardinals. “It is no personal merit of mine that this honor has come to me,”said the new Cardinal. “The sovereign pontiff desires to reward the good children of Chicago.” Mundelein became the first Cardinal west of the Allegheny Mountains. Joining him in this station was the Archbishop of New York, Patrick Joseph Hayes.

In Tehran, the holy men of a different faith took to the streets to protest attempts to establish a republic. Brandishing signs reading “Down with Republicanism” and “Long Live Islam and the Shah,” they viewed the creation by their parliament of a more representative government as “another British weapon introduced to undermine the Islamic faith.” Supporters of the republic also accused the British, but, in this case, of fomenting civil unrest to serve their needs. By the end of the week, a compromise had been reached to depose the current Shah but retain the present form of government by installing his younger brother in the role.

Someone who’d have relished the opportunity to pour out his sins before leaders of any faith was Harry Thomas. Dubbed the “champion confessor,” he made his 283 confession before Judge John R. Caverly for crimes “ranging from burglary to murder.” It was believed the state’s attorney would pursue the death penalty if Thomas was convicted of the latter.

One crime Thomas couldn’t take credit for was the disappearance of President Calvin Coolidge’s cat Tiger, or Tige for short, from the White House. Having darted out into a snowstorm, the beloved feline was believed lost, but a S.O.S. sent out over the radio led to a quick recovery. The cat received a new collar with the words “White House”stamped on it.

Week Fourteen: March 30-April 5, 1924

New truths about African animals formed the heart of a lecture by Carl Akeley at the Field Museum. Having returned from a three-year expedition to the continent, with several specimens that he intended to stuff and mount, Akeley shared how wrong some of his and presumably the audience’s preconceptions were. The lion was not vicious, but brave, a protector of its territory and indifferent to man. And the gorilla was of a “gentle, kind, and inquiring nature.” He regretted having killed three—a male, female, and their offspring—for the museum. “Shooting gorillas is about as much sport,” Akeley remarked, “as shooting blind and crippled women.”

In the fourteenth week of 1924, most violence was man made. In Romania, while in the middle of addressing more than a hundred business leaders at the Economic Institute, banker Aristide Blank was assaulted by a mob of fifty young men. They were part of a large wave of Antisemitic violence cutting across Bucharest in the wake of the trial of a man accused of attempting to murder a prominent Jewish newspaper publisher. As the young men beat Blank, they shouted, “Hurrah for Henry Ford,” the American car manufacturer from whom they’d gleaned their worldview.

A similar spate of violence greeted the election of the village board in Cicero, just west of Chicago. On the night before voters went to the polls, armed men stormed into the office of the Democratic candidate for village clerk and pummeled him with the butts of their revolvers, while the candidate for village president barely escaped being shot. Kidnappings and beatings of poll workers and voters marred election day as Democratic and Republican candidates vied for the control of the village and, more importantly, its 143 saloons, operating in defiance of the Volstead Act.

Allied with the Cicero Republicans was a transplanted South Side Chicago gang led by John Torrio. One of his associates, Frank Caponi, or Capone, didn’t make it to the ballot box. Caught in a shootout with a squad of Chicago police, brought in to restore order, Caponi took one in the heart and dropped dead into the prairie grass outside the enormous Western Electric plant. Four days later at the funeral held at the Prairie Avenue two-flat he shared with his mother and brother–Tony “Scarface” Caponi, also known as “Big Al” Brown, operator of the notorious Four Deuces resort–Frank got memorialized with three thousand roses that completely covered the house and the walk leading up to it. In addition to the various members of the Torrio gang, in attendance were some well-known politicians, judges, and Police Sergeant William Cusick whose squad had shot Caponi dead.

Two days prior to the gangster’s lavish funeral, the strains of the popular song “Hula Lou,” could be heard coming from within an apartment at 817 E. 46th Street. The song played for almost two hours straight before car mechanic Albert Annan arrived to discover his wife Beulah standing by the phonograph, the body of a dead man at her feet. The man, she said, was a stranger who’d attempted to assault her, so she shot him–in the back. Under questioning by police, she admitted the dead man was her lover, Harry Kolstedt. They’d spent the afternoon drinking and a lover’s quarrel had turned deadly. Sensing a memorable story, the Tribune had this to say of Beulah Annan, “They say she’s the prettiest woman ever accused of murder in Chicago—young, slender, with bobbed auburn hair; wide set, appealing blue eyes; tip-tilted nose; translucent skin, faintly, very faintly, rouged, an ingenuous smile; refined features, intelligent expression—an ‘awfully nice girl’ and more than usually pretty.”

Whether Beulah deserved to be executed for killing Koldstedt would be up for a court to decide. Wealthy Chicago playboy Augustus Darwin Curtis got what he deserved, not far from Algiers. Curtis had a “hobby for monkeys” and kept “several at his country home near Chicago.” Near Blida he “captured one of the baby apes, hoping to take it home,” but the “parents of the youngster pursued him.” He barely escaped with his life.

Week Fifteen: April 6-April 12, 1924

Illinois voters went to the polls in the fifteenth week of 1924. In the primary election, two of the most contested offices were the Republican nominee for Governor and United States Senator. The Chicago Tribune had led a long campaign against the incumbent governor, Len Small, under investigation for some corrupt practices during his time as state treasurer. In contrast, the newspaper supported the incumbent senator, Medill McCormick, whose family owned the Tribune. Illinois voters did not share the opinion of Chicago’s paper of record.

As the Tribune sourly announced the morning after the election, Governor Len Small “carried Cook county by a substantial margin and reports from downstate indicated that he was victorious there.” The race for the Senate seat was much closer. By Friday of that week, twenty precincts had yet to report their results. Former Governor Charlese Deneen led the incumbent Senator Medill McCormick by 4,091 votes out of over 800,000 cast statewide. Of the precincts yet to report, ten were in Chicago. One was thought to be the precinct where the ballot box was “stolen and is believed to have been thrown into the drainage canal at Thirty-first Street.”

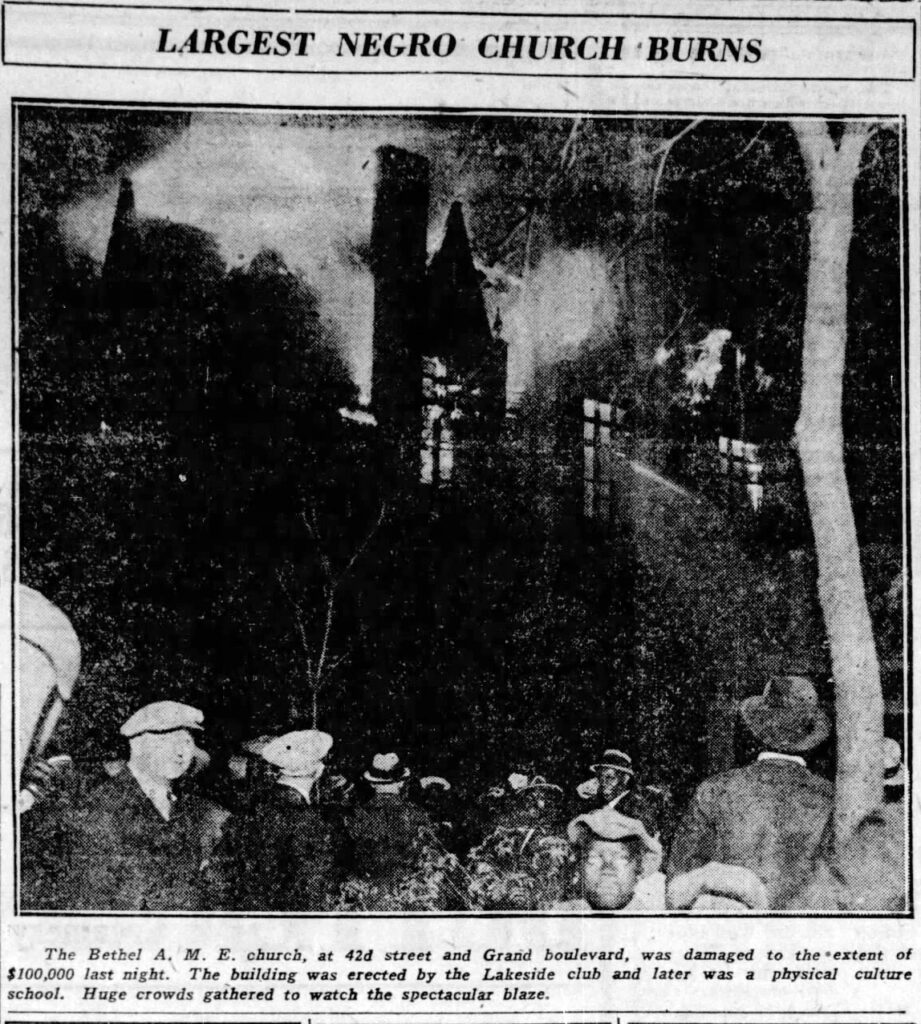

Small triumphed despite a strong push for reform within the Republican Party. Among the leaders of this effort were Chicago’s Black churches. Before the election, twenty churches held events that denounced Small despite his campaign highlighting the appointment of a couple of Black state officials. At Olivet Baptist Church, with a congregation of over 10,000, making it the largest Black church in the nation, the Reverend L.K. Williams denounced Small and his campaign’s tactics from the pulpit.”My people are not to be bought in that way,”said Reverend Williams.”We care more for honesty in public administration than we do for a few favors that may be handed out to certain individuals. We call it an insult to say to us that our chief concern is not a decent and clean conduct of the affairs of the state, but the political prizes we may win.”He noted that Small had the support of the Ku Klux Klan.

And the Klan was sure to take credit for Small’s victory. In the Illinois Fiery Cross, published in Chicago and distributed statewide, the Klan patted itself on the back for helping rally support behind the beleaguered Small. “Even in Cook County with its strong and well organized Roman Catholic, Jewish, Negro, and alien citizen vote, the victory for patriotic Protestantism was almost as great,”the paper noted.

In Italy, another election occurred that week that solidified the power of a party that shared some of the Klan’s worldview. The Fascisti party led by Premier Benito Mussolin took 356 seats in the Italian parliament, far outpacing the second place Roman Catholic party and leaving the various socialist and communist parties with but a handful of seats. All in all, it was a relatively peaceful election in Italy, the Tribune observed, with only one man being killed in a brawl outside the polls at Tivoli.

Week Sixteen: April 13-April 19, 1924

Baseball returned in the sixteenth week of 1924 bringing with it all the promise of the new season. Neither Chicago club got off to a good start on opening day. “No white hosed hero rose above the dust of battle at Comiskey Park,” as the White Sox were defeated 7 to 3 by the St. Louis Browns before a crowd of 25,000. As for the Cubs, playing on the road, the”Chicago entry pulled about everything that could be expected of a minor league outfit in the ninth inning and allowed the St. Louis Cardinals to score three runs and come from behind to win a 6 to 5 victory, much to the delight of some 18,500 rooting natives.” The Tribune predicted that the Cleveland Indians and New York Giants would win their respective league’s pennants that year.

It was a week of fresh starts and looking to the future. In Greece, in time for the centennial of Lord Byron’s death in support of Greek independence, voters overwhelmingly supported the establishment of a republic, abolishing the monarchy. Closer to home, at a banquet at the Congress Hotel, prominent Jewish Chicagoans pledged $150,000 toward a $300,000 campaign to establish a “Chicago colony in Palestine.” Speaking at the event, Mayor William Dever proclaimed,”The Jewish citizens of our city have decided to build a large agricultural colony to be named Chicago to perpetuate the name of our own great and prosperous city and to show appreciation of the advantages Chicago has given them.”

A more pessimistic attitude toward the future was expressed by the announcement that the French were working to revive development of a “death ray,” suspended at the time of the Armistice, ending the Great War, when it was learned that the English were working on a similar weapon, an “invisible radio ray,” capable of downing airplanes and being designed by inventor Harry Grindell Mathews.

The United States Congress feared not an external future foe but rather internal transformation. In an effort to preserve a majority of “Nordic” people and their descendants in the United States, the House of Representatives passed an “immigration restriction bill” 322 to 71. The new law would establish strict quotas on European immigration, tied to 2% of an ethnic group’s population based on the 1890 census, significantly reducing the number of migrants from Southern and Eastern Europe and “tend to make Northern Europe the chief foreign breeding ground of future American citizens.” The bill also excluded any Japanese migration, in defiance of the longstanding “gentleman’s agreement” between the two nations and straining the ties between the two. The immigration commissioner at Ellis Island, Major Henry Curran, when asked for his impression of the new bill declared, “Our gates have stood open long enough. It is time to close them a bit.”

A prominent Chicagoan was having his citizenship investigated that week by Representative Henry Rathbone of Illinois. Star swimmer Johnny Weissmuller’s father had been born in the former Austrian-Hungarian empire, but Johnny said he could prove he was born in the United States, thus ensuring he could represent the country at the Olympics in Paris that summer.

Weissmuller must have welcomed the news that the city council was examining a plan to create a six-mile long, uninterrupted bathing beach along Lake Michigan on the north side of Chicago. It was one of many projects announced that week that could, if they moved forward, profoundly transform the city. The planning commission hoped that Judge O.M. Torrison would dismiss the objections lodged by various landowners and clear the way to “transform South Water street from an alley-like street lined with rambling, ramshackle buildings into a two level riverfront boulevard and heavy traffic thoroughfare, flanked with huge skyscrapers.”

One of those skyscrapers would be the newly announced Jewelers’ Association building, containing the “world’s tallest garage,” with a quarter of its twenty-three stories given over to parking. It would join the Tribune Tower, the new Palmer House Hotel, the Straus Building, and the American Furniture Mart building in transforming the city’s landscape.

Another proposed project promised to give an old building from Chicago’s past a new purpose. The South Park District approved a plan to transform the former Palace of the Fine Arts from the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, abandoned since the Field Museum had moved into its new building a few years prior, into the “largest and finest convention hall in the world.”

Surveying all this growth and transformation. Colonel Robert R. McCormick could confidently predict in an address before the Chicago Association of Commerce that within a handful of years, the city would become the “great inland capital of the United States,” the center of art, science, and commerce for the nation. He attributed the certainty of Chicago’s destiny to its “ideal site”and the resilience of meatpacking, agricultural, tool manufacturing, and the Board of Trade in the face of “hostility from the government of the United States.”

“I can see nothing,” said McCormick, “which can change this excepting some great cataclysm such as had vast influence on other great nations and that is extremely unlikely.”

Another individual who earlier in his life had dreamed of a great future for Chicago died at the age of 68 from heart disease, poor and alone in a cheap hotel on Monday of that week, before any of the city’s grand plans had been announced in the newspapers. Arriving in the city in 1880, architect Louis Sullivan had designed the Auditorium Building, Chicago Stock Exchange, Schlesinger & Mayer department store, and Transportation Building at the 1893 World’s Fair, among other structures, forever transforming architecture in Chicago and the nation.

His last work would be reviewed in that Saturday’s paper by Tribune book critic Fannie Butcher, who proclaimed Sullivan’s recently published The Autobiography of an Idea “one of the few great American biographies.” “There is something peculiarly sad in the thought that the man who wrote this really great book should have died just as it was about to be given to the world,” Butcher observed, “a monument to him which will be firm and steady when the work by which men knew him by shall be crumbled.” Within days of his death, Sullivan was buried in Graceland Cemetery, with members of the American Institute of Architects and the Cliff Dwellers Club serving as the pallbearers.

Week Seventeen: April 20-April 26, 1924

On Easter Sunday, prominent Chicagoans promanded along Lake Shore Drive, the “acknowledged parade ground for wealth and fashion,” in the seventeenth week of 1924. The holiday had fallen later in the year than usual, but the day was a cool one, with many forced to wear their winter coats. Men strutted about in silk hats and morning coats with “white carnations and gardenias in their buttonholes.” The hats the women wore remained small while green was a “popular color this spring, in all its shades.” Reflecting these trends was the ensemble of twenty-one-year-old Elizabeth Paepcke, née Nitze, who looked “unusually lovely in a reseda green cloth coat trimmed with dark fur, and a small black hat”that she wore to services at Fourth Presbyterian on Michigan Avenue.

A slow steady progression, like that of the Easter Parade, characterized the career of motorman Edgar Dickens, who marked 50 years of service on the city’s streetcar lines. It was believed that over the course of a half century–which had seen public transit go from horse- to cable- to electric-powered–Dickens had traversed 1,822,500 miles, “all of it here on Chicago car tracks.” Dickens, 74, observed the occasion on his regular 69th Street line.

A New Yorker with a fondness for Chicago marked his own milestone that week. Chauncey Depew, the former head of the New York Central Railroad and United States Senator, turned 90. He attributed his steady, healthy progression through life to his personal “philosophy.” “This is a pretty good world, and the people in it are pretty good people,”Depew remarked. “If you cultivate a sense of humor and the right outlook you won’t get dyspepsia or insomnia, and most of your troubles come from them. Most of the things that could upset us if they happened, never happen.”

Something upsetting did happen to twenty-three-year-old Wanda Stopa that week, cutting short her progression through life. It had started with tremendous promise. Born to a respected artist and a mother descended from minor nobility, Wanda grew up in a comfortable home within the Polish enclave on the northwest side, achieved academic success, and became, after attending law school, “Chicago’s youngest woman attorney.”

Wanda became intrigued by the city’s bohemian neighborhood, clustered around the old Water Tower. She started to frequent artist studios, teahouses, and cabarets. She married a ne’er-do-well Russian “count,” who mistreated her, but found comfort in the companionship of another fixture within the city’s creative community, advertising man Y. Kenley Smith.

The much older and married Smith regarded Stopa as the “brainiest girl” he’d ever met and, when she gave up her career as a lawyer, supported her financially. According to friends, Smith was a “romantic humanitarian” who supported several struggling artists and bohemians. Wanda took this as a sign of his love and, aware of his unhappy marriage, became determined to wed him.

All of this led to an encounter between Stopa and Smith’s wife, Vieva, at the latter’s cottage in Palos Park. Feeling ill, Vieva refused to engage with Stopa, who was demanding the Smiths divorce. When the cottage’s caretaker, Henry Manning, a sixty-eight-year-old former architect whose career and family had been destroyed by his alcoholism, attempted to intervene, Stopa pulled out a .38 caliber handgun and shot him through the cheek, killing him. Before Stopa could turn the gun on her, Vieva jumped through a window and ran for help. Reached at his office in the Wrigley Building, Smith could only react in horror at the death of Manning and attempted murder of his wife.

Wanda disappeared. The police hunted her, but the search did not last long. Within a day she had been discovered dead in a room at the Hotel Statler in Detroit. She had ingested cyanide. The Tribune blamed Chicago’s bohemia for this tragic sequence of events. Wanda’s mother, Inez, the blood of Polish nobles flowing through her veins, felt otherwise, saying of Y. Kenley Smith, “no gray haired man, no matter how rich, who makes love to a little girl while he has a wife is anything but a bum.”

Week Eighteen: April 27-May 3, 1924

Shouts of “You’re a liar” met Health Commissioner Herman Bundesen when he suggested at a public meeting of the city council’s health committee that “vaccination was necessary for the prevention of epidemics.”For over three hours, the gathered “medics–homeopaths, allopaths, neuropaths, osteopaths, and chiropractors–as well as cult leaders, anti-vaccinationists, and others fought over the merits of their respective theories.”

They had come to protest the proposed creation of a city board of health, one of many reforms supported by Mayor William Dever. In the eighteenth week of 1924, Dever and 1,000 of his supporters celebrated the completion of one year in office with a large party at the Edgewater Beach Hotel, in the former judge and alderman’s old ward, the 49th.

A year prior, the Democrat Dever had defeated the Republican incumbent, William Hale Thompson, largely perceived as being corrupt. Once in office, Dever set out to reign in crime associated with bootlegging, root out the graft present at almost all levels of city government, and champion the consolidation of public transit lines and implementation of the Plan of Chicago.

Dever stood in stark contrast to many of his fellow politicians. Illinois Governor Len Small had been accused of various crimes but managed to be renominated in the recent Republican primary. In neighboring Indiana, Republican Governor Warren T. McCrary learned that he didn’t share Small’s luck. A federal jury found him guilty of mail fraud–the result of a somewhat complicated scheme in which the governor had bilked Hoosier bankers out of close to a million dollars–and the judge sentenced him to a $10,000 fine and ten years in the penitentiary in Atlanta. In handing down the harsh sentence and having McCrary immediately remanded into custody, the judge pronounced “there is no difference between the lowest criminal and the highest.”

That didn’t seem to be the case in Washington that week. While congressional investigations into various misdeeds committed by members of the former Harding Administration and the current Coolidge Administration continued, a jury took only a few hours to dismiss charges against Minnesota congressman Harold Knutson. He had been arrested the previous March after having been discovered in the company of a much younger government clerk in the backseat of an automobile parked along a remote stretch of country road in Virginia. Knutson claimed he’d done nothing indecent but did admit to offering the arresting officers money in order to make the whole matter go away. “I didn’t want the headlines in the papers saying ‘Congressman Arrested!’ regardless of how malicious the arrest might be,”said Knutson, who also worried about what his elderly mother would think.

While corruption didn’t seem likely to tarnish the reputation of Chicago’s mayor, Dever couldn’t control larger forces at play that might sink his administration. A bulletin released by the Chicago Crime Commission reported that 86 murders had occurred in the city in the first 91 days of 1924–almost a murder a day. The Commission noted that in the previous year, 270 murders had occurred in all of Cook County, but only 129 suspected killers were indicted by grand juries. The Commission blamed the slow, uneven pace of justice for the uptick in crime.

One person whose day in court would not be delayed was Mrs. Belva Gaertner, accused of the fatal shooting of automobile salesman Walter Law while the two were together in her car. As the trial began, the defense asked that the automobile, the scene of the crime, be released from police custody to Belva’s husband, which the judge denied. The Tribune noted that Belva “appeared in court garbed in the same fashionable suit and hat which she has worn on other occasions.”

Week Nineteen: May 4-May 10, 1924

Duchess, an Indian elephant aged somewhere between 85 and 90, dropped dead while eating her afternoon meal of hay in her “winter home, the monkey house,” at the Lincoln Park Zoo. She had been at the zoo for over thirty years, after being gifted to the city by P.T. Barnum. A call for a replacement elephant went out immediately, and Duchess’s remains were sent to the Field Museum where her hide would be removed, preserved, and put on display. All Chicago mourned her passing.

The slow, quiet death of Duchess matched the mood of the beginning of the nineteenth week of 1924 as various stories unfolded with little urgency or drama behind them. A Princeton astronomer threw cold water on the notion that the radio could be used to communicate with life on Mars for the simple reason that there was no life on Mars. The canals that amateurs claimed to see on the planet’s surface were merely the product of the “defective human eye or the imperfect telescopic lenses.” A French astronomer claimed, however, that Mercury could be inhabited. “The heat and light on Mercury are seven times more intense than on the earth,” he said. “But the atmosphere surrounding the planet is so compact that their effects may be less violent.”

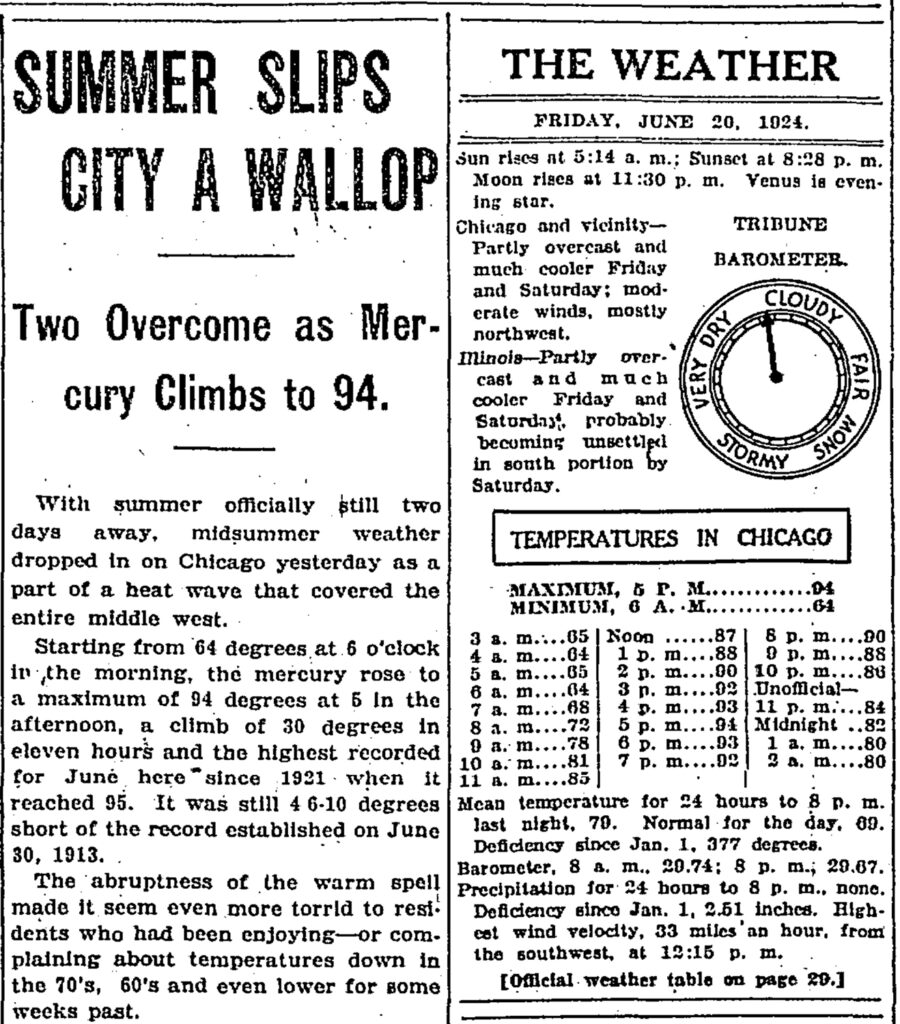

Closer to home but no less heated was John Phillip Sousa’s testimony before the House of Representatives patent committee that Prohibition had killed the light opera, which almost always contained “drinking songs of the rollicking kind.” According to the band leader, “we can’t write them nowadays as, apparently, the inspiration is lacking.” He was there with composer Victor Herbert to testify to the detrimental impact radio broadcasts were having on the sale of music–why would anyone buy sheet music or a recording when one could listen for free to a song on the radio? And by the time a listener did get around to buying the music, it would be waning in popularity due to overexposure on the airwaves.